In theory you'd think that every car would be on the same line; after all there is only one fastest way through a corner, isn't there? Well, yes - and no. Some drivers take one line, others take another. The reasons are numerous. In the seconds it takes a driver to round a corner you can witness the very essence of Formula One™ racing. Those seconds provide a window into the strengths and weaknesses of each individual driver and his team.

Next time you get the chance, watch for a while. One car goes wider than another, maybe brakes later; some dab the brakes, others don't; some exit wider than others. Why?

Grand Prix drivers are like professional footballers or golfers; they are practiced in their art and can pick their line within a couple of inches. David Coulthard, for example, goes deeper into a corner than Kimi Raikkonen but exits slightly wider. Why? If they don't all take the same line it must be for a reason.

Of course, when it comes to car behaviour and drivers' preferences there is a

complex relationship between front wings, the end plates, turning vanes,

suspension pick-ups, traction control, wishbones, sidepods, undertray and rear

wings. The tyres play a crucial element too and their characteristics are an

integral part of the mix. But let us start simply, with the most important

relationship of all, that of the driver and his car.

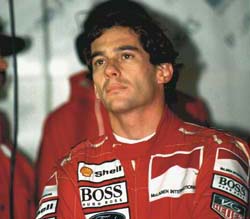

Triple champion Ayrton Senna started his analysis of a circuit by comparing the positions of the corners to the longest straights. That may sound obvious, but it is crucial. His thinking was this: although every milli-second is crucial, there is little time lost on a corner compared to the many seconds that can be lost on a long straight. So how a chicane (such as Turns three and four at the Nurburgring) is taken depends on whether there is a long straight before it or after it. If it is before, then he liked to carry the speed into the corner, brake late and deal with the problems of car control on the exit. But if the long straight followed the chicane he preferred to brake earlier, set up a tidy exit and get on the power early to make the most of the straight. If you are on the power later you are not only losing time in the corner, but you then lose it all the way down the straight as well.

Like all drivers Senna divided the actual corner itself into three sections: entry, mid corner and exit. Conventional thinking is that there are two options: fast in and slow out or slow in and fast out. That means that if you are tidy (ie slower) going into a corner you can afford to pick your exit line, set yourself up and then tread on the gas and deal with problems on the way out. Then there is the reverse; if you carry a lot of speed into the corner (ie going faster) you take the benefits on the way in and, in theory, it should cost you on the way out; the reason being that because you go in deeper, you have to turn in tighter, therefore you are later on the gas and lose time from there to the exit.

When it comes to talking to their engineers drivers refer to either 'oversteer' or 'understeer'. Oversteer is quite literally the feeling you have over used the steering (hence oversteered) and the evidence is the back end of the car stepping out. This is a result of the car either having too much grip at the front or not enough at the back. Understeer is the opposite; where you feel you have not used the steering enough, (or under steered). So you turn in and the nose of the car keeps going straight. This is the result of too little grip at the front or too much at the back.

In an ideal world drivers want a car that is fast in and fast out. And the corner indicates the fruits of their labours. Of course one of the elements a good engineer has to cater for is the requirements of a driver. Pure physics may indicate one thing but if the driver can't feel it then some compromises have to be made.

Of course you have to rule out the human element first. "We did a test with Johnny Herbert in '94 that would basically decide if he was to drive for us the next year," says Pat Symonds of Renault. "Michael (Schumacher) did some stunning times and Johnny was right there with him until the last two corners which are pretty fast. He said he wanted to make changes because the car didn't feel safe but I told him that Michael was taking the corners okay so it was possible and he should go away and think about it. Anyway he tried again without changing the settings and was considerably faster - and very close to Michael's time. He did it basically because of the belief I had instilled in him."

The tyres, of course, are crucial. There are always limits, and in Renault's case this year they are dictated by their Michelin tyres. Their developments have resulted in a better tyre, but one that has lately affected the car's stability on the entry to the corner. But because none of the other Michelin runners is similarly affected it is Renault's problem and not Michelins.

"I can't get the correct balance of the car," said Button at Spa. "The car is a bit twitchy on entry and understeers at the apex which makes it difficult to get a balance."

"The new tyres work a different way and I can't get the car exactly how I want it. Sometimes we think we've got it but when we get to qualifying we're a bit out and with only four runs it is difficult to work your way back."

While those of the ilk of Jean Alesi go storming into a corner and then scrabble out, Button is often compared to Alain Prost and needs his car to be smooth and settled on the way in. "I like a car to be stable at the entry," he says. "I don't mind understeer at the entry but I need it to be stable on the brakes because that is a big part of one lap, braking is where you can make up the time."

With a tighter turn in than Trulli's, any instability is going to cost him.

"My initial turn-in is a bit sharper but that's the only difference," Button

adds. His travails brought to mind the misery of last season, but he smiled as

he realised one of the benefits: "After last year's car I am used to not having

any front end grip."

Surely a sharper turn in makes the car harder to control though? "Yes, but it wasn't a problem at the start of the season but is starting to be now - which is a bit strange," explains Button. "I'm having to be smoother than I was on my initial turn-in."

But with a better car comes more confidence to ride the knife-edge: "Generally I like to have a bit of oversteer now, which I never did before. That means I am able to go late on the brakes too because I don't mind a bit of oversteer on entry. I guess I can do it because I've got more confidence in the car. I know what it's going to do - it's more gradual. Last year it was all over the place."

Check back soon for part two of this feature.